Under the guise of fighting “voter fraud,” former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, Jeff Sessions, fought to suppress the black vote.

The passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965 legally guaranteed African Americans the right to vote. However, due to endemic racism, swaths of citizens in 1980s Alabama remained functionally unaware of this right.

Albert Turner was an African American civil rights activist from Alabama. Turner served as an advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and helped coordinate the historic 1965 voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery. By the 1980s, Turner devoted himself to organizing voter drives and voter education campaigns in Perry County, one of Alabama’s poorest counties. Turner’s efforts bore fruit, and African American voting rates rose significantly.

Enter Roy Lockhart Johnson.

Roy Lockhart Johnson was a white District Attorney in Alabama who served during the time Turner was organizing. For several years, Johnson had unsuccessfully tried to crack down on voter registration efforts like Turner’s. In 1984, having become aware of the climbing African American voting rates in Perry County, Johnson viewed this refreshing increase in representational democracy as a crisis that needed to be quashed.

Through a joint Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit with investigative journalist Jason Leopold, Property of the People obtained records from the Department of Justice’s U.S. Attorneys Office on Johnson’s response to this perceived crisis.

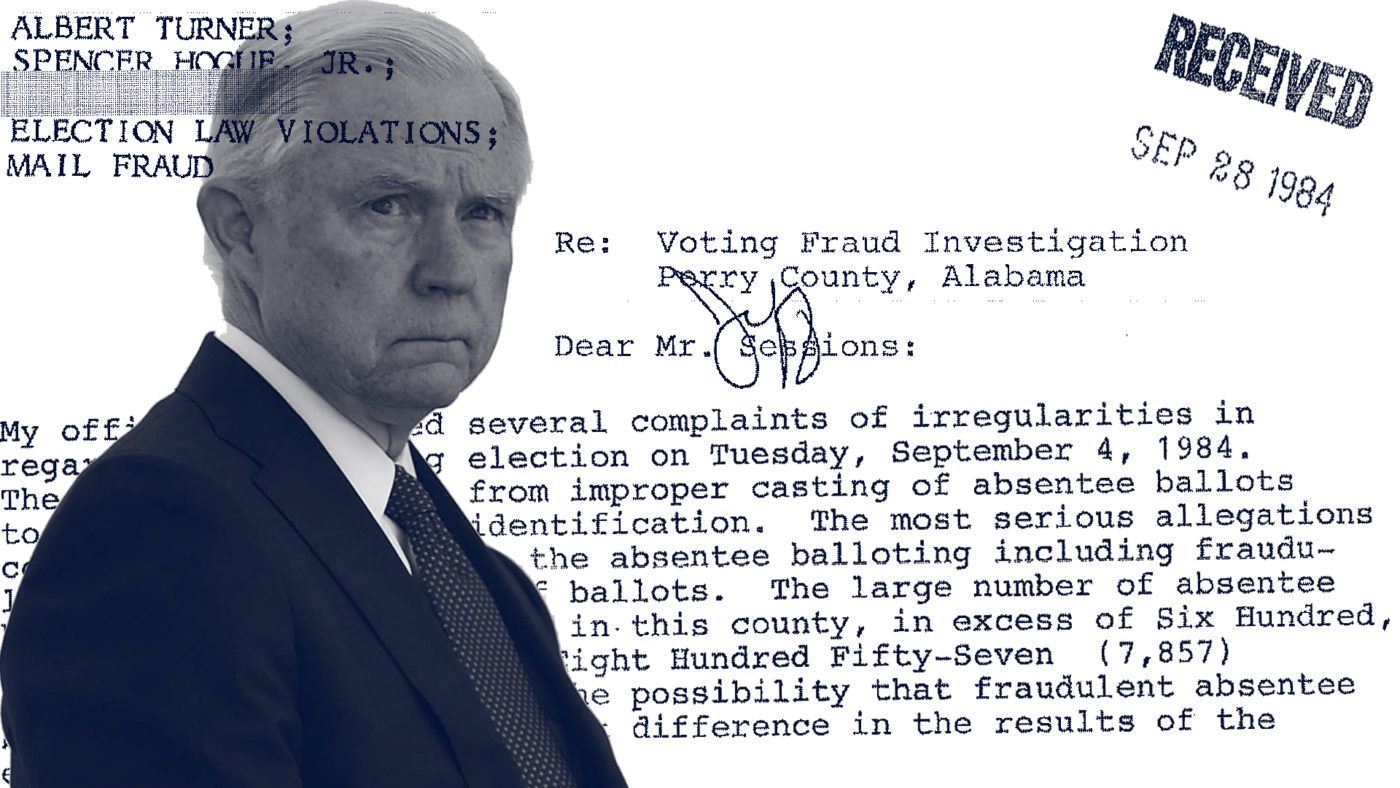

The documents showcase Johnson pleading to then-U.S. Attorney Jeff Sessions for help. In his memorandum to Sessions, Johnson decried “irregularities” during the early voting period for the 1984 election. Specifically, Johnson highlighted for Sessions what he viewed as an alarming uptick in absentee voting – a direct result of Albert Turner’s voter registration efforts in which Turner helped elderly black Americans vote for the first time. “Voting fraud,” Johnson declared to Sessions, was most likely to blame for increased African American voting in Perry County.

In his letter, Johnson declared there was a “need for an extensive investigation into the voting process in Perry County.” He urged Sessions to “consider this letter to be an official, urgent request for all possible assistance in conducting this investigation.” Johnson concluded, “I cannot over-emphasize the importance and the urgency of this request.”

Sessions answered the call.

Persuaded that black voting presence in Alabama was so disturbing as to require a federal action, Sessions had the FBI send roughly a dozen Special Agents to investigate.[1]The DOJ convened a grand jury and served dozens of subpoenas. The FBI even obtained the actual ballots cast by the supposedly suspicious voters, thus violating the secrecy of the ballot. The FBI agents then visited and interrogated many of those elderly voters at their homes. They were terrified.[2]

The FBI’s investigation failed to produce actual evidence of voter fraud. Nonetheless, Sessions and the DOJ pushed forward with federal prosecution of Albert Turner, his wife Evelyn, and their colleague Spencer Hogue Jr.[3]They were referred to as the Marion three.

One of the records recently obtained by Property of the People further reveals that Sessions was informed there had been a suspicious fire in the Turners’ garage during the trial. There is a high likelihood the fire was caused by a bomb planted by white supremacists seeking to intimidate the Turners. The record, a memo drafted by Sessions titled “Turner Fire,” stated the Turners’ car was “engulfed in flames.”

Yet, it does not appear Sessions did anything about it. When poor African Americans dared to vote in rural Alabama, Sessions launched a federal investigation, grand jury, and prosecution. When a possible bomb attack targeted civil rights activists, Sessions remained silent.

The car bomb was never reported and Sessions’ memo remained in his Turner File, never to see the light of day –until now.

At his trial, Albert Turner declared, “This whole FBI investigation of absentee voting and the scheduled trials were set up to stop the political progress of black people in the Alabama Black Belt. The power structure wants to turn back the hands of time in Perry County and throughout west Alabama. I would encourage black people not to let my indictment stop them or discourage them. We need to vote in even larger numbers because they are trying to take our right to vote away again.”

Though Sessions’ racist investigations and prosecutions of voting rights activists in the 1980s were enough to sink his nomination for a federal judgeship in 1986, it failed to halt his appointment as Attorney General under President Trump. Now, as Trump, Sessions, and the broader administration employ yet another imaginary voter fraud crisis to disenfranchise people of color, the history of Sessions’ earlier crusades against voting rights becomes ever more critical.

The full story must be told.

[1]See e.g., Nomination of Jefferson B. Sessions III, to be U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of Alabama, Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary, 99th Congress, March 13, 19, 20, and May 6, 1986, page 278, wherein Senator Denton recounts Albert Turner’s former testimony, stating that 10-15 FBI agents worked for six months on the investigation.

[2]Id., page 205, wherein James Liebman’s testimony describes FBI agents saying to one voter, inside her own home, “Ms. Green, your ballot has been tampered with,” leading a “scared witness to give cautious statements to the FBI.”

[3]United States v. Turner, Hogue, & Turner, Cr. No. 85-00014 (SD Ala. 4 July 1985).